Baffling Easter sign for Australians in New York

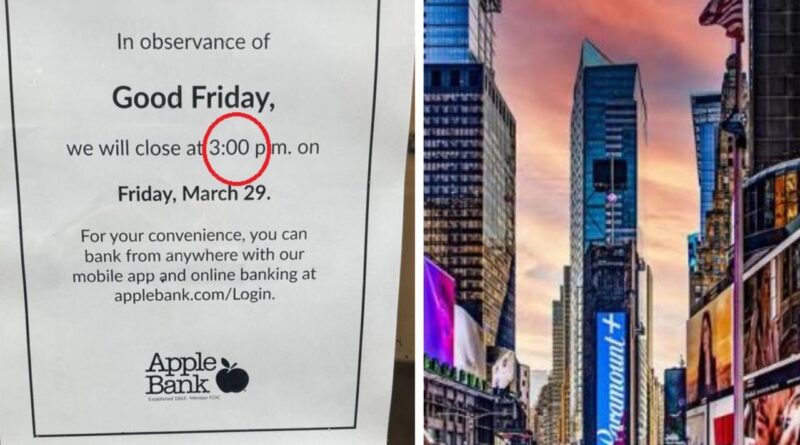

The sign on the window of a bank on the lower east side of Manhattan was much like one you might see on any Australian bank at this time of year.

The kind that would politely inform you that the bank would be shut on Good Friday wouldn’t reopen until Tuesday after all the Easter festivities were done.

Except this sign in New York didn’t quite say that.

“In observance of Good Friday,” it read, “this branch will close at 3pm”.

Not close for three of four days. Just that it would close at 3pm. On Good Friday, one of the holiest days of the Christian year, this bank would shut a mere hour earlier than usual.

But then looking around New York – indeed anywhere in the US – on Good Friday and the entire Easter holiday is baffling for an Australian.

It’s bustling. Everything, everywhere, is open.

On Good Friday, I went to the supermarket, popped into the local coffee shop for a latte, went to the liquor store for a bottle of wine and then went for some drinks with friends in the evening.

In Australia, I could have done none of this.

Maundy Thursday evening, after work, was a mad, anxiety-filled rush around Coles and Liquorland stocking up as if the shops would close on Good Friday and not reopen for a month.

So it seems odd that in the US – a nation that seems more focused on religion than Australia, and whose pledge of allegiance contains the words “one nation, under God,” – would casually dismiss Good Friday, the day when God’s actual son died on the cross.

America ignores Easter

Neither Good Friday nor Easter Monday are public holidays in the US.

It’s not just the holidays. All the other accoutrements of Easter seem far more of an afterthought here.

Take Easter eggs. They barely exist in the US.

Yes, Cadbury – a bit chocolate player in America most of the year – comes into its own at Easter where its Creme Eggs and Mini Eggs are in abundance.

There’s the odd Lindt bunny on the shelves, plastic eggs with toys in, and something called Peeps – a diabetes-inducing neon-coloured sugar confection in the shape of a chick.

But the oversized chocolate egg, that you take great delight in smashing to smithereens and then losing a slither of it under the sofa, are nowhere to be seen.

Finding a hot cross bun can be like searching for the holy grail of baked goods.

I found some at the Bourke Street Bakery, a pie shop that started in the Sydney suburb of Surry Hills and has somewhat miraculously now popped up in New York City.

There you can indeed get a delicious plump, citrusy and fluffy hot cross bun. But it isn’t cheap, costing $36 for six or $6.85 for just one. Compare that to six at Woolies for $4, which speaks volumes to their relative rarity in America.

Myers of Keswick, a charmingly old-time store in Greenwich Village which sells scores of British treats (and in a small nod to the Aussies, Vegemite too), had a tumble of tan-coloured hot cross buns on display. The store’s cat sat on the counter, in front of the plate, as if guarding the buns from greedy customers who might want to excitedly snaffle more than their fair share now they’d discovered somewhere that sold them.

Reason Easter is a US afterthought

America’s seeming indifference to Easter is likely rooted in both tradition and religion – or the lack of both.

In Australia, three of the federally mandated public holidays are all about religion, wheel Boxing Day is linked to it. In the US, just one – Christmas Day – sneaks in.

The US is, very, very officially, a secular state and has been since it was created. All are free to practice religion but it cannot be imposed on anyone.

There is no state religion, for instance.

Even the “under God” bit in the pledge isn’t what it seems. It was added in 1954 and had less to do with praising the Lord and more to do with drawing a line between the US, which had freedom of religion, and its great adversary, the USSR, which did its best to curtail religion.

Contrast this to the UK. While it has religious freedom, one branch of religion is intertwined with its history and present.

The monarch, King Charles, heads the Church of England, which is the country’s “established church” and plays many important ceremonial roles. Senior bishops and Britain’s two Archbishops also sit in the House of Lords and vote on laws.

No wonder, then, that religious holidays have a more heightened role in public life even if much of the public ignores the true reason for them.

Australia does not have an official national religion, but the link remains through the sharing of the monarch and that much of Australia’s governmental framework derives from Britain.

That Christmas Day managed to make the cut in the US as a public holiday at all is partly to do with its sheer religious importance but also the fact the day of the week it falls on changes.

Easter Sunday, is always, as the name suggests, on a Sunday. So it was seen as less of a priority in the secular US to have a public holiday dedicated to it given it wasn’t a work day.

With no public holiday, so fewer Easter traditions have taken root in the US to fill up all that time off. People don’t go away for Easter breaks or home to see mum and dad, hot cross buns are harder to find, kids don’t pine for massive eggs.

Twelve states do recognise Good Friday as a state holiday, but that only means state government workers are guaranteed the day off. Easter Monday doesn’t even get a look in.

The big holiday in the US, the one you can’t miss, isn’t even Christmas – it’s Thanksgiving. The November weekend is the busiest of the year as millions of Americans crisscross the country to visit family.

It’s also resolutely secular. Religion doesn’t come into Thanksgiving at all.

The fact that a bank in New York would close an hour earlier on Good Friday is, in some ways, surprising. Surprising that the company would mark Easter at all, even in such a token way.

The bank staff – and Jesus – would all be chuffed at that free hour, I’m sure.

Benedict Brook is news.com.au’s US Correspondent and is based in New York City.